The next edition of 40 Towns will begin publishing on the Ides of March, but in the meantime here's a one-shot magazine: 10A. 10A is the course hour for my spring literary journalism course, "Ordinary Extraordinary." In addition to prose, we're "reading" photographs, by established masters such as Robert Frank, Milton Rogovin, Diane Arbus, and Ray DeCarava, and by working photographers and documentarians such as Ruddy Roye, Tanja Hollander, and Duncan Murrell who've been responding to student work, including their "Instagram essays" -- pictures+words.

This past Thursday, I sent my students out of the classroom: with a simple assignment: Find someone or something to photograph. Write a true story. Publish by the end of the class. Here it is: a portrait of one hour and fifty minutes within walking distance of classroom Reed 102 at Dartmouth College. Pictures+words. Instagram journalism. True stories, as true as we could make them in the space of one class meeting.

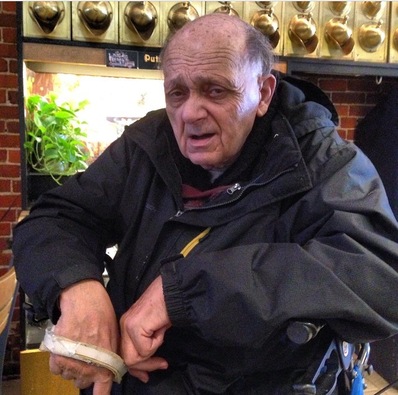

1. A Story About His Cop Days / by Carl Neisser

“Boston got another foot of snow,” he says to a worker shoveling on the sidewalk. The shoveler shrugs him off but I catch up to him as he shuffles away on his walker. He was looking for someone to talk to. I take him up on the offer. “My name’s Carl too. What’s your last name? What is that, Jewish? I grew up with Jews. They’re good workers. I grew up Episcopalian––know what that is? Same as Catholic, but bishops, no pope.” I ask if I can interview him, knowing he’ll say yes. “We’re gonna have to sit down and get a cup of coffee.” “Two sugars, two milks. I’m a New England boy, just like you.” I buy the coffee and he gets us a table. “V-A-L-L-I-N, middle initial F. You ever see an Indian travel card?” I tell him no and he pulls it out of a wallet bulging with twenty other plastic rectangles. “Cherokee on my mother’s side––I’m 30 or 40 percent. They’re a good people.” “I’ve got Parkinson’s Disease. I’m a guinea pig.” Between “Hey, Soul Sister” on the radio and the blender screaming behind me, I’m sitting a foot away from his face, which he keeps covering up with his unrestrained left hand. He mumbles. “They’re gonna take some blood out of me. Those DHMC doctors––they’ve got attitude. Great food there, though.” “I miss my godfather, my friends. My father used to hit us. My mother tried to commit suicide three times.” He tells me a story about his cop days, but I only hear the end: “when all those nurses got killed? Remember that? That was my buddy who broke that. Those were good days.”

2. Her Last Day / by Shoshana Silverstein

Two women are counting change by the register. Cass looks up. “For here or to go?” I tell her I’m a writer. I ask if I can take her picture? She gives me a skeptical look. Her ponytail flips around as she turns away. That’s when Elyse comes out from behind the pastry case. She’s timid, but gives me a large smile and pushes the loose golden tendrils behind one ear. “She’ll do it, it’s her last day. She wants to.” Cass says over her shoulder. Last day of three years. She’s studying to be a vet tech. Like me, she’s a Vermonter. “I like the quiet here,” she says. "but I can’t wait to get rid of the weather.” Her new school is in Florida.// Elyse smiles, turns. Her lip stud flashes light pink. She fiddles with the scale. I’m fairly certain we’re both blushing. We study the croissants.// A man in a light brown Carhartt steps up, orders an iced coffee. Cass says, “It’s Elyse’s last day.” “You’re leaving us?” He throws his arms up. “What are you going to do?” Cass cuts in again. “Run away.” He asks, “Are you going to tell off some costumers before you go?” Cass: “You.” Elyse laughs, says something quietly as she hands over the oversized plastic cup to his oversized hands.// A few Dartmouth students come to the front of the line, and Carhartt moves to put sugar in his drink. I turn to ask him his name, but before I do he’s back in front of the pastry case. “You know some of us rely on a million friendly faces when we come in here.”// As Elyse blushes gently, Cass again steps in, busily ringing up the students’ orders. “Tomorrow is my last day.”// When I ask for Cass's name, she hesitates. This time Elyse steps in. "It's Cass."

3. In the Summer, He Mows / by Kimberly Mei

In the cold my pen has stopped working. I press harder, struggle to scratch out East, then, Sorry, how do you spell it again? Thetford. Like T-h-e-t…The pen is dying, snow is falling, and the faint blue ink is nothing like the blue of his irises. More like the halo of his contacts, which cling to pinkish eyeballs as they follow the movement of my pen, digging at paper in an attempt to write down the name of his hometown. // In the summer he mows. But for now, it’s this white stuff, mixed to a cookies ’n’ cream gray, that he attacks over and over again in his lean green machine and leaves crumbling in five-foot pyramids. He rules Admin row to just past the River cluster. He starts at 6 a.m. There’s no deadline, but it’s still stressful, the endless mounds of blankness, the sick wet clumps, the deceiving powder sprinkle from the sky. I remember how one morning, still in bed, I heard his metal plow banging into concrete, and dreamed there was a bomb exploding outside my window. // In his hand is an enormous pair of yellow headphones. Hearing protectors, but also a radio, with a fat antenna and an audio jack for an iPod. He listens to 93.9 IMS—current events, you know, but also a little comedy—‘till 10. Then, 70’s and 80’s music. Here, a smile, the wariness fading from the lines of his face for a whole second. But then it’s back. He won’t tell me his favorite song. And after the music, he says, he usually shuts off the whole thing, just listens to silence. // I snap his photo and his face grows even more stern. / Well—thank you, I’ll let you get back to your work. / “Okay, but edit that,” his voice grows louder. “Photoshop it, so I look better.”

4. I Still Wear the Hairnets / by Jordyn Turner

Darin started working at Dartmouth College’s Collis Café nine years ago. She has a husband and kids, but her coworkers are her family. She tells me about each of them and I listen, the painted characters realized by figures standing, working, idling, talking, listening around me, her words coated with a palpable pride. “Food’s been a part of all of our lives.” There’s Ray, whose mother is a chef and owned a restaurant – two, actually. She and Darin bicker all the time – in jest – but students who don’t know any better sometimes think it’s real. Darin looks at Ray and remembers the bewildered face of a student behind the glass who looked on helplessly in the wake of a play fight. “She thought we were serious!” // The introductions continue against a backdrop of order-ups, playful insults and the constant buzz of conversation. There’s Dave, whose family owned a pastry shop. And Jackie, who looks over and smiles at the sound of her name; she caters for Blood’s Seafood on her days off. For them, this is more than stir fry and omelets; it’s a taste and sound and bustle and camaraderie that feels like home. “DDS doesn’t want us to be called lunch ladies. That’s why they got rid of the whole hairnet thing, ya know? Gave us these baseball caps.” Darin’s not wearing one. She gestures at Dave, who is. They come in green or black, with the words ‘Collis Café’ embroidered in multicolored letters over a gray skillet. She shrugs, cocks her hip. “But I still wear the hairnets. I’m a lunch lady and happy to be one.”

5. Domesticity is for Dogs and Rabbits, She Said / by Tara Wray

When I was about to get married, an 80-year-old widow pulled me aside and whispered in my ear: don't do it. She got married and ran a household and raised children and repressed her desire to become a veterinarian so women like me wouldn't have to (I don't want to be a veterinarian). Domesticity is for dogs and rabbits, she said. Not educated, interesting women with half a brain. You do have half a brain, don't you? // Some days I don't do laundry at all. I let breakfast crusted night shirts pile up on the floor next to the washer where the dog can sneak in and lick them clean. When I do get around to washing and drying a load, I let that clean pile grow so large that it swallows up all the socks in the entire house. // If I were a rabbit I would hop into the forest and hide within a rotten log and nibble clover and bluestems and have 27 babies, most of whom I would eat alive. // I read a story this morning about a little girl who was born with half a heart. She died at five years old, after enduring 3 operations on her half-heart. I bet her parents would give anything to be bored by the the day to day activities of daily living.

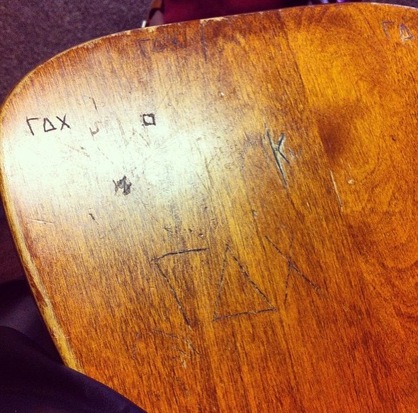

6. What Does It Take For Someone to Carve His Masculinity So Deeply?

/ by Charli Fool Bear-Vetter

One of the first things anyone told me when I got to Dartmouth was: “Don’t go to GDX, they have an Indian head on one of their pong tables and the brothers are kind of scary.” Nothing against any of those brothers, but it is advice I’ve heeded. // I grew up surrounded by men who exerted masculinity in every act. They wouldn’t wash the dishes, they wouldn’t do the laundry, and they wouldn’t hug each other. I never really understood how two people who love each other can’t bring themselves to hug because it’s “gay.” The first time I saw my grandfather cry, it was a funeral and it was in secret and he was angry that I saw it. His mother had just died, but he was upset by the fact that I somehow saw him as less than a stoic, manly Indian. // What does it take for someone to carve their masculinity so deeply? Was it a Women & Gender Studies class? I took WGST 10 in this room (Thornton 105) when I was a freshman, and I remember so many male athletes sitting in the back, rarely contributing except to argue with a point. They weren’t always bad or offensive opinions. In fact, many made beautiful and feminist points in our discourse. But some would sulk on the sides, and I wonder if this is the work of one of those men from so long ago. // One of my family members once told me to stop acting like a dyke. In the same breath, he told me I wasn’t enough of a lady. Was I meant to exert femininity as much as he pushed his masculinity onto his surroundings with his severed, preserved deer heads and a case full of rifles? // I don’t think masculinity should be so violent.

7. Look Close, and You'll See the Fissures / by Lacey Jones

She was writing about holding her breath while playing. Then she started writing about other moments when she couldn’t breathe. The email she got from a friend after the second death on campus: worried about how we were supposed to move on, about how we would inevitably move on. // Sometimes she sits in KAF and watches CNN instead of working. The mundane ruptures with news of the latest massacres, then she drags the edges of the ordinary closed again. Sometimes “the bubble bursts.” // She was writing about holding her breath while playing the violin. Last night, her wrist twinged during practice. Her breath catches, here, again, and her eyes grow red. She’s crying. “I can’t imagine not being able to play,” she says. She wishes she'd practiced harder. At age four, during middle school, freshman year, last week’s lesson. “Then I would at least be good, if I had to stop.” // Last night, I was interviewing a youth minister for a story, and he spoke about his brother: violist, conservatory, then tendonitis, and everything ended. Everything could end, here, too, but now we are talking about a government test and the edges are closed again. // Lately, I’ve been thinking about drowning. About holding my breath until it sours in lungs that burn. Lately, I’ve only been good at controlled pain: drowning when I can still see the surface. Lately, her surfaces are starting to tear. “Try hard now, because there could be no later,” she says, and it is so cliché it shines. Polished. Smooth. Look close and you’ll see the fissures.

8. Scrape. Stop. Scrape. Stop. / by Katie Williamson

I spot the shovels first. Big, red plastic blades, with pale wooden shafts and red handles clenched in the hands of three men. The red is almost too bright against the muted winter grays. Then there’s the noise. Scrape. Stop. Scrape. Stop. The shovelers are rhythmic and purposeful, removing last night’s slush. “We work where we’re needed,” says Brad. He works for the Hanover Inn. He’s worked there seven years. He lives in Orford, NH with his wife and teenage son. They like to hunt and fish. Not ice fishing. “I have a bit of a phobia of ice.” He returns to shoveling. Little blue crystals of ice and salt tumble into rows. Once, he and his cousin were out walking on the Connecticut River when they encountered a big hole. The ice was slippery. They almost fell in. “It was scary,” he says. Raises his eyebrows. Not as scary as losing his parents last spring. They died within three months of each other. “It was a tough time,” Brad says quietly. He looks straight ahead. “But” — something returns to his soft, tired eyes, “I’m thankful for my parents.” His great grandfather was also from Orford. He used to own a stagecoach route from North Haverill to West Lebanon. “Sometimes I’ll look at the pictures inside the Inn and see if one of them’s my grandfather, ‘cause I never met him.” I can’t picture a stagecoach. Sounds classy. Like the violinist Brad met when she stayed at the Inn. “I don’t know why she sticks out, but she does.” His shift ends at 5pm today, 10pm tomorrow. “You never stop learning,” he says.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed